Early Convict Coal Mines and Settlement

Newcastle 1802

Be for hear is maney one that hav Benn hear for maney year and thay hav thar poor head shaved and sent up to the Coole river and thear Carrey Cooles from Day Light in the morning till Dark at Knight, and half starved, but i hear that is a Going to Be put By, and so it had need, for it is very crouell in ded [1]

.....So writes Margaret Catchpole of the miners of Coal River in January 1802. Margaret Catchpole was a friend of botanist George Caley who visited the Coal River Settlement on an expedition in June 1801. The men mentioned by her above were possibly Irish rebel convicts who had caused Governor King so much concern, however the records don't reveal their names. Margaret Catchpole's information predicting the Coal River camp would be 'put by' was indeed correct for the fledgling settlement was soon to close.......

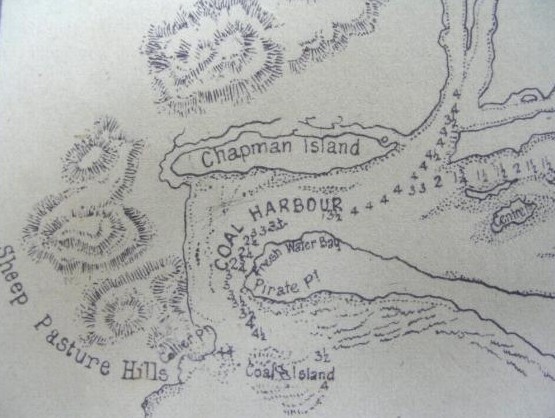

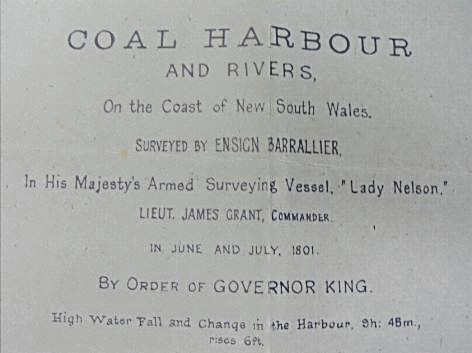

Just a few months previously in June 1801 a survey expedition to the Coal River led by Lieutenant-Colonel William Paterson and including Lieutenant James Grant, surveyor Ensign Barralier and miner John Platt explored the area and brought back favourable accounts of the coal resources and settlement site.[2]

Ensign Barralier's Map of the Coal Harbour

The First Settlement under Corporal Wixstead

Governor King determined to establish a settlement at the river mouth with the intention of mining coal to contribute to financing the colony. [3] A new penal settlement would also allow for the separation of worrying Irish political leaders from the main colony.[4]Corporal John Wixstead, a corporal of the NSW Corps was selected to establish the settlement. He arrived at the Hunter River on the Francis with eight privates and 12 prisoners about 23 July 1801

John Wixted had arrived in Australia with the First Fleet as a marine aboard the Sirius. He was with the Sirius when the ship was wrecked at Norfolk Island in 1790. He resigned from the marines in April 1791 and joined the 102nd Regiment of Foot made up of marines who had decided to stay in Australia. He served five years in 102nd. In April 1798 John Wixted received a grant of 260 acres from Governor Hunter on the banks of the Georges River near Bankstown, however in 1800 he re-enlisted as a private in the NSW Corps and was promoted to corporal in June 1801 shortly before he was sent to the Hunter River.

Soon after their arrival at the Hunter River the brig Anna Josepha arrived on her second visit for a cargo of coals and timber.

Governor King had been good enough to forward two casks of porter and with this and refreshments of a more solid nature, all the people assembled on shore and celebrated the establishment of the small settlement on the present site of Newcastle. At this time there must have been upwards of 65 persons in the place. As well as 30 free persons, there were 28 seamen on board the brig and eight on the schooner......as soon as the two vessels left the harbour, laden with coals and timber, Corporal Wixstead became unpopular through favouring some of the convicts more than others. A letter was sent to Governor King containing a series of charged as to the free indulgence of spirits and the bad behaviour of some women who had been allowed to accompany the expedition [5]

In May 1802 Wixted and his group were withdrawn from Newcastle and it was almost two years before another attempt was made to settle Newcastle.

John Wixted saw service in Van Diemen’s Land for several months in 1803. In September 1807 he was back on detachment in Newcastle. In July 1808 he was promoted to sergeant. He remained in Newcastle until March 1810. Months later Sergeant Wixted and his wife Ann returned to England after 22 years in Australia

Surgeon Martin Mason

Governor King being compelled to take notice of the anonymous letter writer charging Corporal Wixstead, replaced him with surgeon Martin Mason. Mason was of bad reputation and was known to be a cruel man. He arrived at the Coal River with Ensign Barralier and Deputy Surveyor Charles Grimes in September 1801. The Governor's aide-de-camp, Mr. Frederick Kirkwald also joined the voyage. [6]By October 1802 four extra convicts were sent, making a total of sixteen men [7]

Three of the men were miners and six were employed carrying the coal. They had no wheelbarrows and the tools were badly constructed, needing repairs already. Vessels loaded straight from the beach. Mason suggested to Governor King that a saving could be made if mining were to continue on an extensive scale, by having a path made with slabs from the pit to a wharf 'run out upon a bank of stones and sand'. Mason had noted that the coals were better in quality the further the men went underground and he had intentions of extending the mines further. He requested small candles of the type commonly used in coal mines, large scales to weigh the baskets and six box barrows that would hold two hundred weights each [8] (this is the equivalent of 100 kilograms each barrow).

In November Mason would report to the Governor that he had 3,820 baskets of coal at hand. He estimated this amounted to 190 tons (if the baskets held one hundred weight each). With three miners and three carriers he was raising about 9 tons a day from four different mines. One mine was 34 yards under ground; one was 31 yards; one was 27 yards and one was 10 yards. He told Governor King that he could set nine more miners to work immediately and with one man to draw for each miner, could raise 190 tons per week. The strata of coal they were working on was 3 foot high, out of which there was one inch of clay and other rubbish, with 22 inches of neat coal; over this there was a strata of 18 inches of good coal. Mason writes of opening another mine further around in Fresh Water Bay. Hugh Meehan, master of the Anna Josepha had built sawpits in Fresh Water Bay in April [9]. Mr. Palmer's sloop loaded nearby.

Here at Freshwater Bay, Mason tells King, 'where there was a strata of three foot neat coal under the above two strata, the coals were of superior quality'. Mason sent back to headquarters a cask of coal as example and envisioned that he could 'open mines to set twenty men to work in Fresh Water Bay; if there are not minors in the colony then many ruffens may be made good minors'

Government Settlement Abandoned

Surgeon Mason regarded John Platt as a 'good working miner, but criticized his foresight -'he cannot see much further into the ground than his pick cuts'. Mason needed a skilled surveyor to explore the hills and ascertain where to 'conduct mines to save labour and carrey of the water' to the best advantage. Despite these enthusiastic plans, Mason's stay at the River was short - King refers to his 'improper behaviour' and Mason was removed at the end of the year leaving a guard of five privates at the river. [10]Although official settlement was withdrawn, miners remained at the River. Coals were obtained by private vessels and small quantities for government use. Miner John Platt was employed by John Palmer and in May 1803 the Sydney Gazette reported enthusiastically that

A new mine has been found at Hunter’s River, which is likely to yield an abundance of the finest coal that has ever been witnessed. The discovery was made by J. Platt, a miner in the employ of J. Palmer Esq., and a quantity of coal was brought round by the Edwin.'[11]

Perhaps John Platt had followed Martin Mason's advice after all and examined more closely the land up from Freshwater Bay. In 1805 Platt gave an account of mines then in operation -'

The coal mines on the sea side Government House, Newcastle are 3 ½ feet thick, solid coal, and resemble those of Bushy Park between Warrington and Prescot. The same mine is also in Lord Derby’s Park near Prescot called Nozeley Park. The coals are of the best quality and are used for furnaces, malt houses, being free of sulphur. Those (coals) at the harbour by the salt pan called New Discovery from it being like a Delfi in Weston near Prescot in Lancashire are of bad quality having as much dirt as coal and fit for burning bricks and fire engines .[12]

Second Settlement under Lieutenant Menzies

By 1804, the possibility of establishing valuable commercial enterprise coupled with a desire to remove the worst of the Irish insurgents from Sydney district in the aftermath of the rebellion at Castle Hill, encouraged Governor King to re-settle Coal River. A young naval Lieutenant, twenty-one year old Lieutenant Charles Menzies requested command of the settlement and Governor King thinking him equal to the undertaking eagerly accepted the offer.Governor King and his family made a special excursion to Sydney harbour to farewell Lieutenant Menzies and his little fleet.[13]

Over thirty Irish rebels from the Castle Hill uprising formed the convict work party.

Under Menzies' directions, the rebel convicts were put to hard labour and at first were kept under tight discipline and control. Security at the settlement was strict in an attempt to prevent desperate convicts absconding and to increase supplies of coal for the government.

Despite this there were plans by six convicts in June 1804 to overtake the settlement and kill the Commandant and soldiers. Two of the perpetrators - Bryan Riley and Andrew Tiernan took to the bush in a desperate bid to escape punishment (Andrew Tiernan had been sentenced to 500 lashes or as many he could take with causing death). The Sydney Gazette reported that Reilly was captured in the bush near the settlement in a wretched and most deplorable condition. He gave an account of the death of Tiernan - that he fell a victim to cold, fatigue and famine, after wandering for some time through the trackless woods and feebly partaking in spontaneous herbage, which might have been impregnated with rank and deadly poison.[14] Find out more about the Second Settlement here

The Settlement under Charles Throsby

In March 1805, twelve months after second settlement, thirty four year old Charles Throsby took over command. His instructions from Governor King included the hours of work that were required of convicts - they were to haul coal from daylight (sunrise was approximately 6am) till 8 a.m, from half-past 8 till noon, and from 2 p.m. to sunset which in March in Newcastle in 1805 was about 5.50p.m.[15] Huts were built or being built by this time as in 1805 Throsby makes mention of them in some of the many orders he issues.The convicts were almost certainly hungry. Supplies to the settlement continued to be a problem for the remainder of the year; when fly moth destroyed wheat crops in the rest of the colony inhabitants at the River suffered rationed wheat portions too. To make matters worse grain supplied from Sutton, the storekeeper at Newcastle was full of dirt. Throsby permitted convicts to cultivate gardens near their huts, however many of these may have been destroyed in December in the same 'hurricane' that caused such damage to the mine entrances, filling them with earth and other debris.

Sufficient clothing was not sent from head quarters in winter and Throsby arranged that those he had personally observed most in need would receive slops first. Oil had also been in short supply for some time obliging Throsby to put everyone, including himself, on short rations.

Little wonder the prisoners tried to escape. Throsby was aware there were plots to abscond and he issued orders for all convicts (fifty-five men and six women at the July 1805 muster) to be in their huts by 8pm each evening for muster. The proprietors of the private huts (where many convicts lodged as there were no convicts barracks as yet) were responsible for the conduct of all residing in their hut; They were liable to forfeit their hut to Government if they failed to report absentees [16]

Thomas Brady who was sent to Newcastle in 1804 was one of these hut owners.

These strict conditions did not deter those who were determined to be free. Thomas Desmond an Irish rebel - an 'inflexible and audacious fugitive' possibly sent with the first group in March '04 was one who continued to attempt escape. With great determination he was to try again and again for the next decade or more.

There were many hundreds of convicts who over the years toiled in exile at Newcastle. They were employed in cedar getting, making salt, burning lime, and general labouring work around the township, wharf and mines. At the coal mines skilled miners were employed underground, however others were required to wheel coal to the wharf or load it onto the ships.

Commandant Lieutenant John Purcell

Lieutenant Purcell was appointed Commandant in 1810. Select here to read about the settlement under the command of Lieutenant Purcell. Over the next few years conditions for the convict miners at Coal River improved little. Illness and disease plagued the convicts. A building was in use as a hospital however it was inadequate and often unable to provide beds or bedding. Convict Surgeon Richard Horner was in charge until 1811 when William Evans was appointed.Evans reported convict patients to be in great distress. Their rations were inadequate and they suffered dysentery in summer, bitter cold in winter and chest complaints all year round. Monotonous drudgery was broken only occasionally by special events such as Governor Macquarie's visit in 1812 or perhaps one of the many shipwrecks.

Government Mines Handed Over to the A. A. Company

In 1830 the government handed over its Newcastle coal mines to the Australian Agricultural Company and coal mining became the most profitable arm of the company for the rest of the century. The A. A. Company's First Mine was located above the Dudley Seam on the corner of the present Brown and Church Streets. [17] Select here to find John Armstrong's Map of Newcastle showing the location of the mine.By 1831 they were in full operation. The mines were being worked by convicts until this time however the company found that convict labour was inefficient and insufficient and began to recruit miners from Britain as well.(40) Although it wasn't for some time that the miners would gather sufficient power to strike for improved conditions, in 1833 there was a glimmer of united hope at least when they jointly applied to Sir Edward Parry for adequate clothing, although his response could not have been what they hoped for. Select here to find a list of A.A. Company Coal Miners in Newcastle in the 1830s - 1840s

There was a labour shortage in the Company in the 1830's particularly when assignment was severely limited late in 1838. Adequate supply of coal could not be maintained and the company was forced to commence an immigration program because of dislike by colonial labourers of underground work.[17]

The Commercial Journal reported in 1840 -

Great inconvenience and delay has of late been occasioned, by the Australian company not being able to supply coals in sufficient quantities for the numerous vessels now lying at Newcastle. The chief cause appears to arise from the feeble and worn out state of their assigned servants, occasioned by excessive labour and the small allowance of rations awarded them. These miserable creatures have every appearance of 'Walking spectres' - such woe begone and wretched objects are scarcely to be met within the colony. An allowance of 3s per ton has been offered these men to perform extra work; but their strength will scarcely carry them through their regular work, setting aside over time labour. They can only be compared with an over worked horse, who, despite all whipping, is unable to job one step farther. We have numerous instances of men belonging to the Company, committing offences for the mere purpose of getting into ironed gangs, in preference to remaining in their service. We consider that if these men were governed by persons disposed to serve the Company instead of themselves, things would go on much better [18]

References

[1] Letter to Mrs Cobbold from Sydney, 21 January 1802. p2. State Library of New South Wales.[2] Perry, T.M., Australia's First Frontier, Melbourne University Press, Victoria., 1963, p57.

[3] Historical Records of New South Wales. vol. IV. Hunter and King. 1800, 1801, 1802. Edited by F. M. Bladen. p. 205 - 206, Governor King to Sir Joseph Banks (Banks Papers)

[4] D.F. Branagan, Geology and coal mining in the Hunter Valley 1791 - 1861, Newcastle History Monographs No. 6. Newcastle Public Library, 1972, p19.

[5] Newcastle Morning Herald 10 December 1897

[6] Newcastle Morning Herald 14 December 1897

[7] Historical Records of New South Wales. Vol IV. Hunter and King. 1800, 1801, 1802. Edited by F. M. Bladen. p620 - 621, Governor King to the Duke of Portland Sydney, New South Wales, 14th November 1801

[8] Historical Records of New South Wales. Vol. IV. Hunter and King. 1800, 1801, 1802. Edited by F. M. Bladen. p 597 - 598Mr. M. Mason to Governor King (King Papers)

[9] Historical Records of Australia, Series 1 Vol. III p772

[10] Historical Records of Australia, Series 1, vol. III, p.406. Governor King to the Duke of Portland (Despatch No. 6. per American schooner Caroline; acknowledged by Lord Hobart, 24th February 1803) Sydney New South Wales, 1st March 1802

[11] Sydney Gazette 8 May 1803.

[12] Sydney Gazette 5 May 1805

[13] Sydney Gazette 25 March 1804

[14] Sydney Gazette 5 August 1804

[15] Historical Records of New South Wales, Vol. V, King 1803, 1804, 1805. Edited by F. M. Bladen, Lansdowne Slattery and Company, Mona Vale, N.S.W.,1979. p. 571.Governor King to Major Johnston (King Papers), 15th March 1805.

[16] Historical Records of New South Wales, Vol. VI, King and Bligh 1806, 1807, 1808. Edited by F. M. Bladen, Lansdowne Slattery and Company, Mona Vale, N.S.W.,1979. pp. 836 - 841 Throsby's General Orders (King Papers) 3rd April, 1805 to 14th February 1806.

[17] Turner, J.W. Coal Mining in Newcastle 1801 - 1900, Newcastle Region Public Library, 1982.

[18] Commercial Journal and Advertiser 22 August 1840

↑