Crossing the Liverpool Ranges

John Henderson - 1830s

John Henderson of Her Majesty's Ceylon Rifle Regiment arrived in Australia on the Florentia in August 1838 [1].

John Henderson of Her Majesty's Ceylon Rifle Regiment arrived in Australia on the Florentia in August 1838 [1].

In his publication Excursions and Adventures in New South Wales With Pictures of Squatting and of Life in the Bush he described the voyage and arrival in Port Jackson.

In Sydney he witnessed the execution of the seven men who had been found guilty of the massacre of Aboriginal people at Myall Creek.

Soon afterwards, at the height of summer he embarked on a journey from Sydney to the Hunter River. He described the voyage to Morpeth and his subsequent journey to the Liverpool Plains...

Having embarked on board one of the Maitland steamboats at night, I had the satisfaction to find myself by breakfast time a little beyond Newcastle, and steaming quickly up the placid river.

He arrived on the steamer at the small village of Morpeth. Having brought his horse with him, he rode up to Maitland from Morpeth and after spending a day at Maitland proceeded to Patrick Plains to the residence of a gentleman friend. Here he stayed about three weeks visiting most of the surrounding country side and when his host expressed a wish to visit his sheep station in the Liverpool Plains to superintend the sheep shearing, John Henderson determined to accompany him.

They packed their saddle bags and started after breakfast on a very warm February morning. By nightfall they had reached Muswellbrook and after staying the night in a 'wretched inn' they began again the next morning. They reached the house of an acquaintance by sunset where they remained for the night.

The next morning they commenced the journey after breakfast and travelled for some miles over flats and undulating countryside known as the Downs where there were a large number of petrified tree trunks standing on end and projecting from an inch to a foot above the surface. They passed the deep but empty bed of a creek called Kingdon Ponds and then the burning mountain of Wingen and in the afternoon came to some very high and steep ranges known as Waldron's Ranges at which point they dismounted and led their horses.

They travelled upwards of 30 miles without finding water and were parched by the time they arrived at the house of another acquaintance where water was obtained. They continued on however as sunset was fast approaching and they wished to stay a little further on. The next morning they set off at sunrise and proceeded three or four miles to the Page Inn where they breakfasted. From here they began their journey over the Liverpool Ranges.....

About Chapter VII

I must not omit to state, that our yesterday's route had been not on the Hunter, which turns to the north-west, but up the Page, a branch of the former river, and coming from a north-east direction. The Page Inn is the last on the road, and near the head of the creek (for none of these can be called streams), from which it takes its name, being in fact the last location in this direction within the colony, so called. Here, in addition to the Inn, is a small store, a post-office, and that great essential in such a country, a blacksmith's shop. This little village (if it deserves the name) is very prettily situated, being by far the most romantic in its appearance of any landward settlement I had yet seen. It nestles in a small narrow valley, bounded on each side by picturesque hills, rising abruptly around, and crowned by bare and precipitous rocks. The channel of the Page (now scarcely boasting of one stagnant water-hole) winds its course through this vale, and in wet seasons leaves the foot of the mountains.

As we stayed rather long at this Inn - in fact, till nearly ten o'clock, we found the heat very great on preparing to start; and the proposal, therefore, to rest till the heat of the day was over, was readily agreed to by me. At lunch, we had for company an unfortunate settler, or rather, a beginner, who was just commencing to experience the troubles of settling. He was travelling up the country with his drays, but his bullocks had been lost for some days, and he had scoured the ranges and gulleys in all directions round, without finding them. He seemed to think that his being a beginner, or (as it is termed) 'new chum,' had been taken advantage of, and that his teams were 'planted,' that is, secreted, in order that a reward might be offered for them. This is a very common occurrence, and was very probably his case, but I never heard how he managed, or what was the result.

By two in the afternoon we got under weigh; and, after a few miles' ride, arrived at the foot of Liverpool Range, - a long and high series of hills over which the track passes, forming the boundary between the colony and the large tract of level country called Liverpool Plains. The first object that struck me here was an immense collection of trunks of trees, evidently felled with the axe, and deprived of their branches. I was at a loss to assign a reason for so much labour having been bestowed (in vain, as I thought), in felling and piling up these useless heaps of timber, till my more experienced friend informed me that every dray descending the range on that side, had a tree attached by way of a drag, - a precaution rendered necessary by the steepness of the descent. Thus, in the course of eight or ten years, during which this line had been known and used, a large space had been strewn with the shafts of gums.

On different parts of the range, which here presents a very steep ascent, there a long rugged ascending pull, and further on a precipitous descent, we passed several drays bound for the interior, each with its team of eight oxen, straining and pulling to surmount this formidable obstacle: but apparently with little effect. There were but small loads on the drays; the last one, which I observed in particular, having only a few bags of flour, salt, and sugar, a plough, the men's bedding, a small keg of water for their use, and a tarpaulin, which had covered the bales of wool on the downward journey. In the rear was slung an iron pot, with two or three tin quart pots, to boil their tea in, and as many pint pots to drink out of, while beside these swung a bullock's horn full of grease for the wheels. The bullock driver flourished his whip of green hide on the left, or near side of the team, while his mate hallooed and belaboured the cattle with a stick on the off side, and the bulldog bringing up the rear, completed the group. The poor animals seemed scarcely to move the dray, while the men shouted at the top of their voices, cracked the bullockwhip, and banged the sides of their beasts of burden without mercy. On such occasions, no quarter is shown to the wretched creatures; and if, after all, they come to a stand, the driver will give them a rest or spell; then, throwing his cabbage-tree hat in the air, as a signal that this time it must be 'do or die,' he seizes his whip, and carbonadoes them from head to heel, an operation he continues till the task is accomplished, or both he and his oxen are knocked up. If he fails to make them proceed, he has nothing for it but to unyoke his team, and camp for the night.

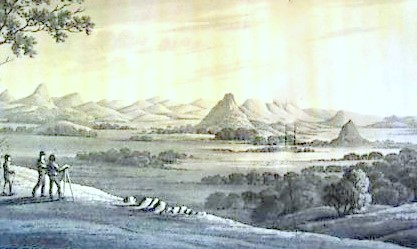

When two or three teams are together at such a pinch, they are yoked together, and drag up the drays one at a time, and when one is alone, the load is sometimes divided into two or more lots, and taken up by successive journeys. After a hot and toilsome pull, we arrived at the top of the range, when I was repaid for my fatigue by a fine view, different from anything I had as yet found in the colony, and all the more admired because unexpected. In truth, I had seen nothing heretofore worth calling a fine or extensive view, and the eye, wearied by the dull unpicturesque gum-trees which so uniformly clothe hill and dale, longed for open and naked scenery, where the very bareness and sameness would by contrast be beauty and variety. Here, then, I was at length gratified. At our feet lay ten or twelve miles of flat wooded country; beyond that extended a wide plain, level as a bowling-green, and without a tree or bush of any kind; and further on, far as the eye could reach, were spread similar plains, divided from each other by low wooded ranges.

The scene was altogether so different from the country through which I had been travelling heretofore, that I was much struck with it, and, despite my love of my native mountain-scenery, imagined it must be a delightful place to live in. Whether it is so or not, the sequel will show.

Near the foot of the range the track divides into three, the one to the left leading to Warra, the cattle station of the Australian Agricultural Company; that to the right proceeding to the Peel, the Company's headquarters in this district, and thence to New England; while the middle one, which we pursued, strikes upon the Mooki, a branch of the Namoi, and continues till it meets the latter river.

By night-fall, we passed the first station on Liverpool Plains, and entered first on one or two open spaces, and then on the first plain, known by the name of Breeza Plain. Before entering on the plain, we turned aside to water our horses at a lagoon with whose position my friend was acquainted; but alas! water there was none; for the lagoon, formerly a deep pool, was, by reason of the drought which consumed the land, quite dried up. There had been 'death in the pot too,'' for the breeze that cooled our faces, evidently did not blow over a bank of violets. Our weary steeds would have been much rejoiced by a drink of water, but there was no remedy, so turning again to the track, we pursued our way across the thirsty plain. The moon shone brightly, and served to guide us; and, in truth, we needed all her light, for the plain so black and like a harrowed field, scarcely left the track distinguishable. No grass, or herbage of any kind, was to be seen; no dew-drops sparkled among our horses' feet, 'like orient pearls at random strung;' the dust rose at every footfall, and the few lean gaunt cattle that crossed our path, as they returned to the forest from slaking their thirst in the Mooki, seemed to the dreamy midnight fancy of a tired traveller, to stalk along the plain - the ghosts of the departed, or the demons (alas poor wretches, they were only the victims,) of the great drought.

By midnight, the barking of many dogs gave evidence that we approached a station, and soon after crossing the bed of the Mooki, which is only a few feet below the level of the plain, we reached, a hundred yards further on, the bark hut called Breeza Station, and occupied by a low man of no very enviable character. My friend, however, had been there before, and had, on a former occasion, been of service to this individual. Moreover, this was no time to be particular, and our position, the jaded state of our horses, the lateness of the hour, and the want of all Inns formed excuses more strong and numerous than were necessary. We therefore knocked the sleepers up, and got admittance.

While they were preparing such a supper as their means and the lateness of the hour admitted of, we unsaddled and rubbed down our horses, and hobbling them with hobbles which for that purpose we carried with us, we turned them loose to ruminate on the bran and maize left far behind, and to chew the cud of bitter reflection - the only thing they seemed likely to chew in such a desert. Having seen that they got a drink at the solitary pool which the Mooki here could boast of, we returned to the hut, and having eat heartily of the simple fare set before us, we lay down each on his sheet of bark and rolled in a blanket, and, despite the hordes of nocturnal visitants, snatched a few hours of broken, not gentle, sleep, the consequence of our toilsome day's march.

In the morning, I was enabled to inspect the establishment and the country around. In front lay the Mooki, which, in the best of times, more resembles a broad deep ditch than anything else; while at present it was only a chain of stagnant ponds, boggy and muddy, and far apart, the spaces between them being often perfectly dried and baked by the sun's rays. Beyond, stretched the plain we had crossed the previous night, appearing, in the dim haze of the morning sun, of great magnitude, though in fact only eight or nine miles across, in the direction we had come. Behind the station rose a scrubby and wooded range, dividing this plain from others further on. The station itself appeared miserable enough, though like most others in this quarter. The hut was of the usual gumslabs, rough as split from the tree, and so far apart that the hand might be thrust through between each. These were sunk half a foot in the ground, and nailed at the top to the wall plates, which rested on round posts, about seven feet high. The floor was earthen - not of trodden clay, but gravelly, and full of holes, - while the roof, of course, was composed of the customary bark, which is stripped from the trees in lengths of from six to eight feet, and laid on the sapling frame like Brobdignagian tiles, overlapping each other, and crowned by saddle-sheets sitting astride the roof-tree. There were only two apartments, 'a but and a ben,' divided by a partition of slabs, and having a doorway, but no door, while a small room, or, as it is called, 'skillean,' leaning against the back of the hut, served as a store and servant's room. In the principal apartment, a hole cut in the slabs eighteen inches square, served as a window; and the man having a wife, this window was ornamented by a small curtain, though, as the woman was a slattern, and, in fact, an old convict, the drapery was none of the cleanest.

A similar hut was occupied by the men, while a stock-yard, with a gallows for hoisting up slaughtered bullocks stood behind, and a dirty sheep yard, fenced with bushes and boughs of trees, exhaled odours not far off. Cultivation or garden there was none, but these were not to be expected, for no crop, and seldom any vegetables, will grow in Liverpool Plains. I was informed that the cattle came every day from the forest across the plain, a distance at many points of ten or twelve miles, in order to drink at the Mooki, whence they returned towards evening, to look for the withered herbage under shelter of the trees. The sheep, too, had to be driven every day across this plain, and brought back at night; but even after all this toil, they could not get wherewithal to fill their bellies. In Liverpool Plains great quantities of a small low tree called 'myall' are found. It is generally about the thickness of the wrist, or arm, and its wood, which has a peculiar smell, and is partly black and partly yellow is much prized for making the handles of stock-whips. Of the leaves and young branches of this tree the sheep are very fond, and in this season it was customary, and indeed necessary, for the shepherds to cut them down for their flocks; while the apple-tree was felled for the working bullocks and other cattle which lingered near the stations.

At Breeza, I found a black girl (one of the aborigines) tending a flock of sheep, and I was informed that she did her work very well. Proceeding along the Mooki, we arrived, after two miles ride, at a bark hut, dignified by the name of store; and here, having previously learned that there were bushrangers out in the neighbourhood, my companion bought a gun and some ammunition, for neither of us had brought any arms. This purchase was made more with a view to increase the stock of fire-arms at the station than to be of use to us on the road, and we were lucky in being able to procure this, as there was little else in the (so-called) store. The fact is, it was chiefly an establishment for 'sly grog-selling,' sheltered under the garb of a bush shop, or store, but at this time they were out of everything, even rum.

Journeying on, we crossed several plains, divided from each other by belts of trees. One of these, Battery Plain, takes its name from a large rock rising abruptly with perpendicular sides from the level ground below. It is crowned with trees, and, from its strangely isolated position, looks not unlike a fort, or battery. Passing a station called Carroll, we crossed the River Namoi, now merely a chain of ponds, but having a deep bed, and in wet seasons appearing a large and rapid stream. Here our route lay for some miles through level forest land. Having crossed the river more than once, and passed over several alternate plains and strips of forest, we arrived, after a ride of thirty-five or forty miles, at my friend's station, well pleased with the prospect of repose, after so hot and fatiguing a journey.

Excursions and Adventures in New South Wales With Pictures of Squatting and of Life in the Bush : an Account of the Climate, Productions, and Natural History of the Colony, and the Manners and Customs of the Natives, with Advice to Immigrants, Etc. By Lieutenant John Henderson of Her Majesty's Ceylon Rifle Regiment p. 180 - 199

Notes and Links

Robert Dixon's Map - TroveGeorge Wyndham's Diary

Settler and Immigrant Ships

Henry Stuart Russell

Sir Thomas Livingstone Mitchell

Robert Dixon

Allan Cunningham

Tamworth Links

References

[1] Sydney Gazette 4 August 1838↑